Private View: 19th of January, 14:00-18:00

Drawing on feelings of isolation and wonder, Maha Ahmed depicts the experience of identity as it is constructed and re-constructed through the narratives of others. Presenting a new body of work for her first solo show at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery Berlin titled An Island of Truths, the Pakistani artist examines the impact of ‘othering’ on the construction of self and the concept of truth when it is contained within specific cultural boundaries. Her intricate, otherworldly visions of fantastical creatures and distant worlds, offer a poignant refection on her personal feelings of isolation, during a period of working and living in Tokyo, and the way in which we can view cultures different from our own.

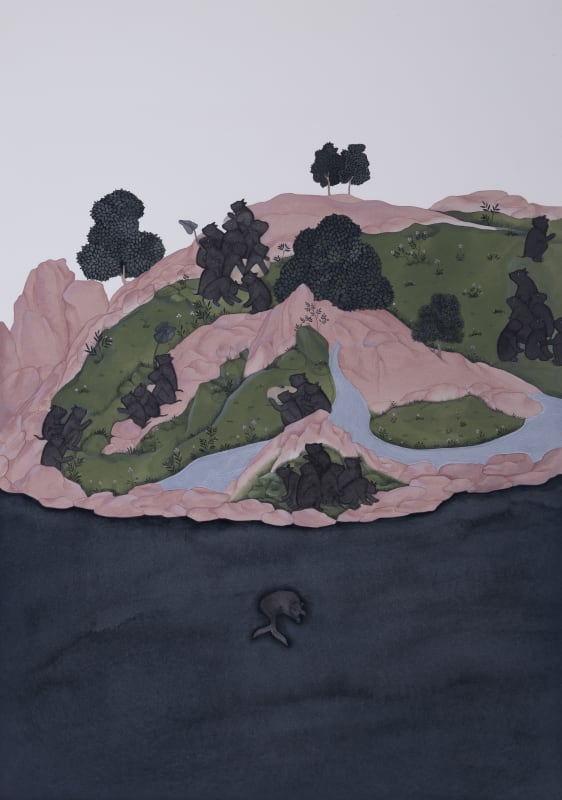

Ahmed dreams up imaginary worlds in which her characters —often mythical or hybrid creatures —arein some way at odds from their surrounding and other inhabitants, thus emphasising the seemingly minor differences that nonetheless create a haunting detachment between individuals sharing the same environment. “This whole imagery comes from my own experiences of feeling different”, admits Ahmed. “In Japan, the seat next to me on the train is always last to be filled because I look visibly different and they’re scared I’ll say something. These little creatures are obviously different, but I’m not trying to make something negative or ugly, I want to make them beautiful". In this way, the artist opens up a discussion around the varying attitudes of ‘othering’ from xenophobia —as is often provoked by fear —to the romanticising of the unfamiliar.

It is through partial understanding, or perhaps the superficial act of gazing without considering the parts that make the whole, which leads to constructed narratives that are internalised by a society or particular group to create a new concept of truth. Using the traditional craft miniature painting, Ahmed employs ultra thin brushstrokes to create delicate, precise details, which aren’t entirely legible from a distance. As such, the viewer is encouraged to approach the work to see the full scene. The paintings change depending on where they are viewed from, thus mirroring the experience of confronting an “other” or being presented with the unfamiliar; the closer we approach the work, the more easily we can see not only the creatures themselves, but also the artistic process through visible brushstrokes. In other words, we are invited to see beyond the first impression and to contemplate the deeper meaning. Importantly, Ahmed’s artworks present us with an alternative way of viewing (whether it be another culture or person, or simply another artwork), which we may consider and carry with us as new knowledge or truths to our own islands.

Similarly, Ahmed’s installation of handmade paper boxes, arranged in a grid on the gallery floor, encourages visitors to have a greater awareness of the space, as they are required to step through the work to reach the paintings. We might consider the installation as a symbol of the invisible barriers, which we place between ourselves and the unknown. Significantly, the artist stresses that it doesn’t matter if these boxes are stepped on, rather the point is to “instigate an understanding of the self within the space.”

Further investigating the construction of identity, Ahmed’s series of character portraits directly references the philosophical concept of ‘othering’, where an individual or group is defined by something that they are not, such as The Portrait of a Monkey that could not climb Trees. “In an ever globalising world, where narratives mix, and we struggle to decide who is right and who is wrong, I am trying to present a visual experience of being the other”, says Ahmed. “It is an appeal to our empathic imagination, and therefore a suggestive point towards a more compassionate politic”. We are reminded, in these paintings, both through their titles and the worlds depicted, of childhood fables and how these narratives are still very much present in the adult world. The experience of being within a strange place can often mirror the experience of the child as we adapt to the space and new ways of communicating both verbally and physically. Through employing fairytale like motifs, Ahmed’s work invites us back into that space of innocence, wonder and learning.

Indeed, her worlds are as beautiful as they are potentially frightening —we are presented with golden skies, shadowy black mass and intense crowds. In this way, Ahmed tackles the complex emotions we might experience in relation to the unknown, such as loneliness, claustrophobia, or liberation and belonging. Ultimately, the viewer is left to interpret the narratives through their own internal experiences and feelings.