Private View: Tuesday 11th January, 6:30-9pm

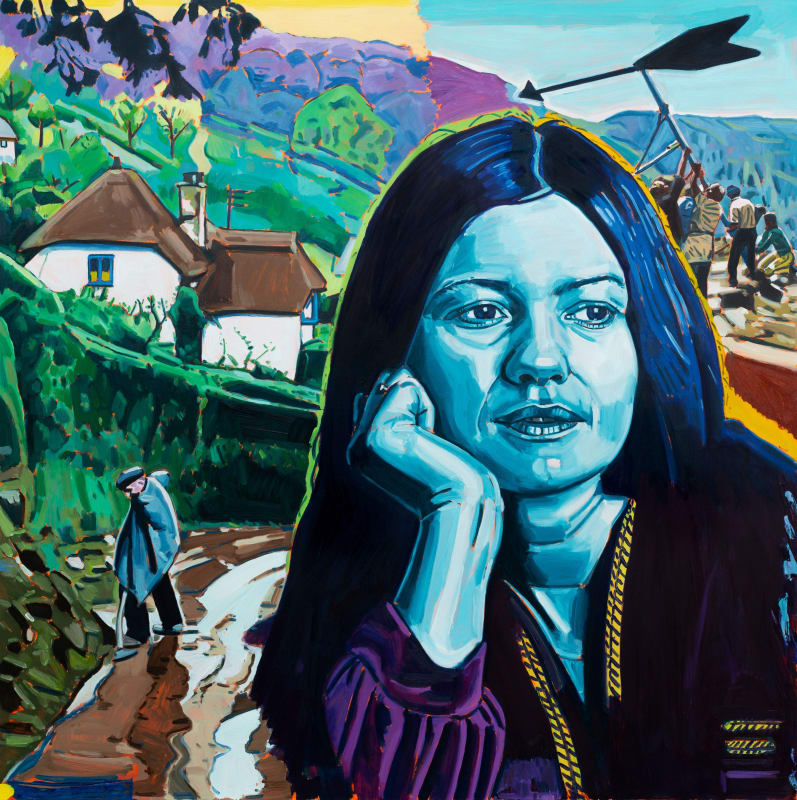

Familiar picturesque country village scenes are rendered surreal against burning orange skies while larger-than-life characters appear caught suspended between visual layers of history. In this latest body of work, Lancashire-born, London-based artist Lulu Bennett explores the concept of the rural idyll as both a contemporary psychological state and a powerful record of a complex past. Rendered in the artist’s signature acid colour palette with spliced imagery, each painting in Period Drama, the artist’s solo show at Kristin Hjellegjerde Berlin, possesses its own distinct narrative and atmosphere, while expressing a wider sense of displacement and anxiety. At the same time, fluid brushstrokes and drips of paint mark a shift away from the hard-edged graphic style of previous works towards a more confident and dynamic aesthetic.

Bennett’s process typically begins with the collection of found imagery from old books and magazines, but while these materials were previously used as visual or atmospheric prompts, the artist has taken a different approach with these latest works by employing a projector to transfer the image onto the canvas. ‘Using a projector simplified the process in some ways, but it also made the act of painting feel more free,’ she says. This creates a palpable tension within the works whereby the compositions appear more structured and cinematic while the gestures of paint are visibly looser, quick and almost frenzied. The painting Never Any Good (titled after a folk song by Martin Simpson), for example, depicts two versions of a father with a son sitting on his shoulders, but while Bennett previously employed sharply defined boundaries to create a strong sense of juxtaposition, here the edges of the images are softer and more fluid. As such, we’re encouraged to draw connections between both the figures and the house looming in the background, creating a sense of history overlaid on the present moment. In this way, the painting, like many others in the exhibition, expresses a psychological experience of time that flows freely between past, present and future, encompassing both personal and collective histories.

During the making of this latest body of work, Bennett was particularly struck by the “doubling up of historical moments” in the 1981 television version of Brideshead Revisited.

While the story is set in the 1920s to 40s, the series is also a powerful reflection of the time in which it was made. Bennett was particularly fascinated by the first few episodes which take place in Oxford and present a ‘Thatcherite vision of Britain as something unreachable, perfect, colonial and poetic.’ ‘It’s deeply problematic,’ says the artist, ‘but it’s a compelling image, and worth examining and understanding as a myth so endemic to the cultural and political landscape of Britain.’ In her work, Bennett captures this complex relationship to the past by simultaneously drawing the viewer into the scene and holding them at a distance. The painting, November, for example, depicts a lone figure standing on a pavement that’s washed over by waves. The work is highly charged with emotion and yet, the cool colour palette serves to both emphasise an overwhelming sense of isolation and create an odd disconnection from reality. Meanwhile, the unusual framing of the work - it almost appears as if it is a painting within another painting - adds a further layer of remove by drawing our attention to the artifice.

This critical engagement with the medium of painting is perhaps most visible in the large-scale painting Cold Poem, which is one of two works without figures. The work depicts a castle in the background while across the bottom of the canvas the word ‘FORM’ appears in bold white lettering nailed onto bright blue breeze blocks with a wilting tulip hooked through the ‘o’. The choice of word is consciously playful, referring both to the act of painting and to poetry. At the time of making this work, Bennett was reading the writing of British poet Alice Oswald, who similarly takes landscape and nature as her subject. ‘She’s currently the professor of poetry at Oxford University, making her the first woman to serve in that role in 300 years. I found something radical in that and also in her approach to everyday, well-worn subject-matter that really resonated with my own engagement with the British cultural landscape,’ she says. In the painting, we see this spirit of defiance in the drips of vibrant red paint that appear caught on the edges of the branches of the trees, and also in the way the edges of the breeze blocks begin to undulate like a liquid slipping from the surface. It is this interplay of more fluid, abstract elements within strong cinematic compositions that makes these works so dynamic and compelling.

‘For me, the concept of a period drama not only describes the work in this show, but acts as a kind of mission statement for my whole artistic project and the evolution of my practice,’ comments Bennett. Indeed, the paintings are less about depicting a specific theatrical event and more about expressing the eternal drama of life.