Private View: Wednesday 9th of February, 6:30-9pm

London (London Bridge)

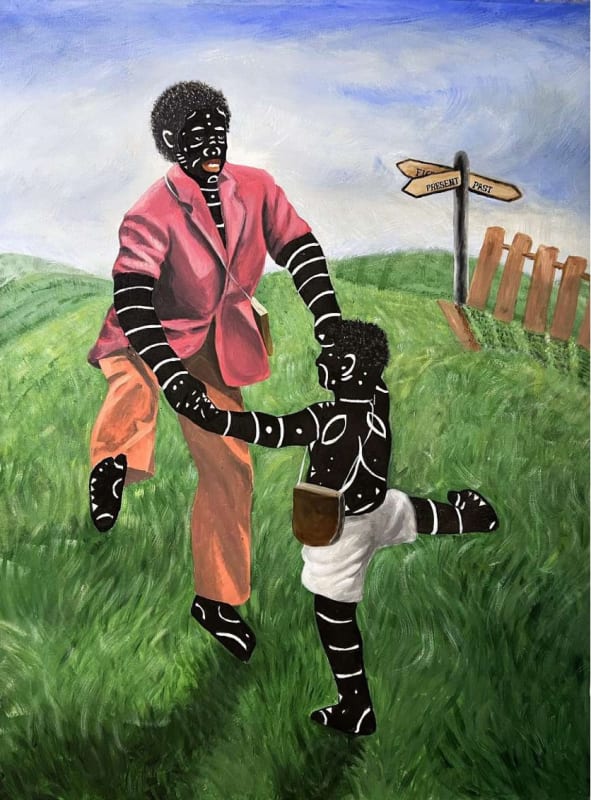

Striking figures appear against vibrant patterned backdrops and tumultuous skies, their black skin painted with white motifs. These arresting mixed-media works by Kelechi Nwaneri are inspired by the artist’s personal experiences and explore relationships with both the self and others through poetic visual narratives. Aptly entitled Finding Balance, the artist’s solo exhibition at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery’s London Bridge space not only contemplates art’s ability to provide space for reflection, but also marks a shift towards a more expressive style in which looser, gestural brushstrokes are employed to evoke a sense of movement alongside the harder-edged graphical details.

As an artist, Nwaneri sees himself primarily as a storyteller, and this particular exhibition centres around the notion of needing to find or restore balance in life and our relationships. Like many of us, Nwaneri recently experienced a period of time in which he felt overwhelmed by the speed at which things were happening around him. One of the most pared back artworks in this series reflects directly on this experience, depicting a man standing with his fingers pressed into his ears while the background is filled with swirling lines that visualise the white noise that surrounds him. However, amidst the tumult, the figure appears at peace with his eyes closed, as if in a state of deep meditation. ‘I see this work as a self-portrait as it very much reflects a point in my life when I realised I needed to turn down the noise and listen more closely to myself,’ says Nwaneri. At the same time, the open space of the white background and the balance between gestural brushstrokes and the defined outline of the central figure serve to direct the viewer’s gaze inwards so that we also experience a sensation of calm and stillness. Significantly, Nwaneri has also created a small-scale sculpture based on the portrait - one of two included in the exhibition - which invites a more tactile engagement, as we are able to walk around the figure. Meanwhile, the white symbols that the artist typically paints onto the skin of his figures and which are drawn mainly from three indigenous languages - Adinkra from Ghana, Uli and Nsbidi from Southern Nigeria - become less decorative and more embedded into the body, appearing as raised lines that wrap around the arms and torso.

Although the motifs are derived from specific, ancient writing systems, much of the imagery is recognisable, and can be interpreted on a basic level. Sometimes the artist selects the symbols for purely aesthetic reasons, while at other times, they are used as visual clues to reveal certain aspects of the narrative. The painting Friendship II, for example, depicts two women in a romantic embrace, each with a symbol connoting their sexual orientation painted onto their cheek as an expression of pride while the figure of a rearing horse - which is used as a repeated pattern in the background - is traditionally associated with strength and passion. The work gains an even deeper significance in the context of severe laws in Nigeria - the artist’s home country - which enforce the imprisonment of any individuals who publicly engage in same-sex relationships, or openly express support of the LGBT community. As such, the painting can be seen as both a quiet act of rebellion and a powerful expression of solidarity.

Many of the works in this latest series also employ brightly patterned backdrops to add to the overarching narrative and evoke a slightly surreal atmosphere. The artwork entitled Oasis, for example,depicts a figure in an upside down bridge posture on the floor, with five people balanced along his stomach. The retro floral wallpaper and tiled floor patterned with red dots play with the viewer’s perception of space by warping our sense of depth and creating a kind of visual chaos. As such, the arrangement of figures becomes a fixed point in the composition, but at the same time, we are aware of the weight that the man on the bottom is bearing. The fact that he is only wearing underwear while the other figures are fully dressed points to both the figure’s vulnerability and the precarity of the situation.

Indeed, in striving to find balance through the act of art making, Nwaneri creates a captivating visual tension between smooth brushstrokes and more impressionistic marks, familiarity and strangeness, simplicity and complexity. In this way, Finding Balance invites us to consider the aspects of not only our personal lives, but also wider society in which the equilibrium might have become skewed in favour of authority, tradition or convention.