Private View: Tuesday 21st February 2023, 6-8pm Berlin

Black figures with white symbols painted onto their skin stand within a vermilion landscape where the earth is scattered with stones and the cacti are blue. For his third solo exhibition at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, Nigerian artist Kelechi Nwaneri transports his signature figures into a futuristic environment on an imagined planet. Red, the show’s title, alludes to the intensely coloured landscapes of Mars, which inspired this latest body of work while also drawing on the associations of the colour with danger, heat, courage and sacrifice. Within this dramatic setting, Nwaneri borrows tropes from science fiction and African Futurism (distinct from Afrofuturism in that it is rooted in Native African experiences and aesthetics rather than the Black diaspora) to reimagine the traditionally masculine role of the explorer as a more fluid, creative individual who seeks to live peacefully with the land.

While Nwaneri’s practice has always involved a process of world-building, his compositions have largely drawn on the myths of the Igbo people of South Eastern Nigeria. The motifs that decorate his figures’ skins combine a mix of three indigenous languages – Adinkra from Ghana, Uli and Nsbidi from Southern Nigeria – in reference to ancient writing systems and fading histories. This latest series of paintings, however, marks a new direction for the artist in which he expands on the storytelling tradition of his ancestors by dreaming up a future existence where humans become multiplanetary. ‘I believe we need to look back to the past to imagine a better and more inclusive future,’ says Nwaneri.

Sojourner 1, for example,depicts a figure holding a large wooden telescope with one foot raised on a pile of rocks. The pose – an almost archetypal projection of bravery and power – evokes that of George Washington, the first president of the United States, in Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851). However, while Leutze’s painting is symbolic of violence and bloodshed – Washington’s boat is en-route to the Battle of Trenton – Nwaneri’s scene is calm and harmonious. His figure is barefoot, dressed in a silvery robe; a blue plant grows from the earth and behind the character there are undulating hills and a fence and watchtower constructed from cut out pieces of raffia matting, which the artist sourced locally in Nigeria. The character in Sojourner 2 is also inspired by a painting from art history – this time Titian’s portrait of Emperor Charles V with a Dog (1533) in which Charles V is depicted in a strong masculine stance, dressed in a lavish costume with his left hand on the hilt of his sword and his right hand hooked through the dog’s collar. Nwaneri’s character similarly conveys a sense of self-confidence but their body language is softer, less imposing. The character wears a purple gown with one hand on their hip and the other lightly touching the back of a robotic dog.

In this series, Nwaneri has not only used recycled matting but also transferred the printed logos from plastic bags that are used to carry water in Nigeria onto the background of the paintings. The plastic bags, he says, are rarely disposed of properly and present a huge environmental problem for the country. In many of the works, the labels remain visible, as murky, floating inscriptions in the sky – a haunting reminder of the devastating effects of continued pollution. At the same time, the artist’s repurposing of waste into artistic material hints at the powerful potential of creative thinking to imagine new ways of living. In this light, his ‘sojourners’ become less conquerors or kings than artists or cultural visionaries who seek to adapt to their new environment rather than destroying it.

This idea is also explored through the series of paintings titled Quarantine. In these works, Nwaneri imagines a period of adjustment in which his figures are depicted in poses of rest as they become more familiar with their environment. The paintings build upon the artist’s previous exhibition with the gallery that considered the importance of finding balance in life and our relationships through connection with others and internal contemplation. In this otherworldly setting, the figures are alone – the harmony they find is within themselves and their surroundings. Quarantine 1, for example, which references Titian’s painting Venus of Urbino (1534), depicts a woman gazing out directly at the viewer, in a pose that is quietly powerful and self-assured.

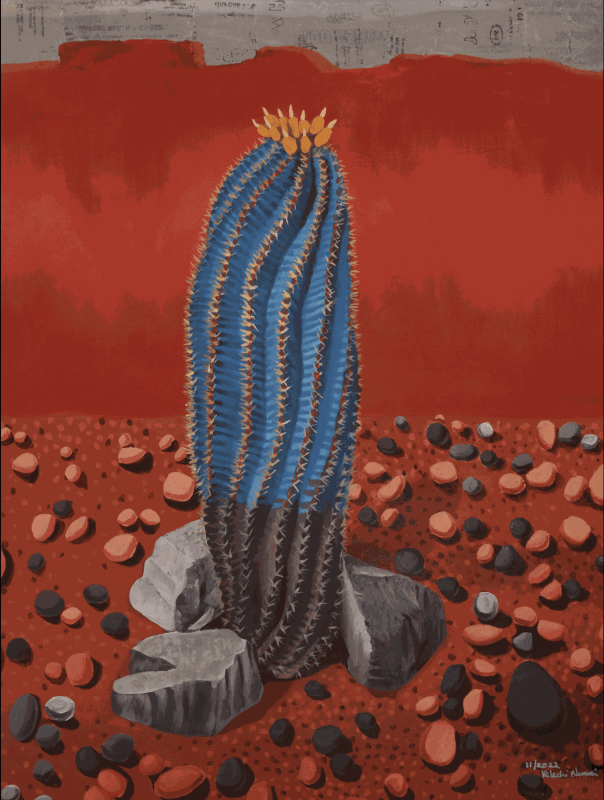

The series No chlorophyll further considers humanity’s relationship to and appreciation of nature. While there are no figures in these paintings, Nwaneri envisions how plant life might exist or be cultivated in a different atmosphere. Varieties of cacti, despite being deprived of chlorophyll, appear thriving in a vivid shade of blue. In one work, the surreal presence of a bright red water post next to a cactus serves as evidence of human intervention. While in the context of climate change, human activity is often associated with destruction, here Nwaneri presents an alternative narrative in which humans are nurturing natural life.

Though these works address the serious and urgent nature of the climate crisis, they are far from dystopian visions. Rather, Nwaneri employs visual storytelling and the lens of African Futurism to highlight the vital role that art has historically played in imagining our future. As he says, ‘When you open up your imagination, there are endless possibilities.’