Private View: Thursday 22nd of September 6:30 - 8:30pm

London (Speak Easy)

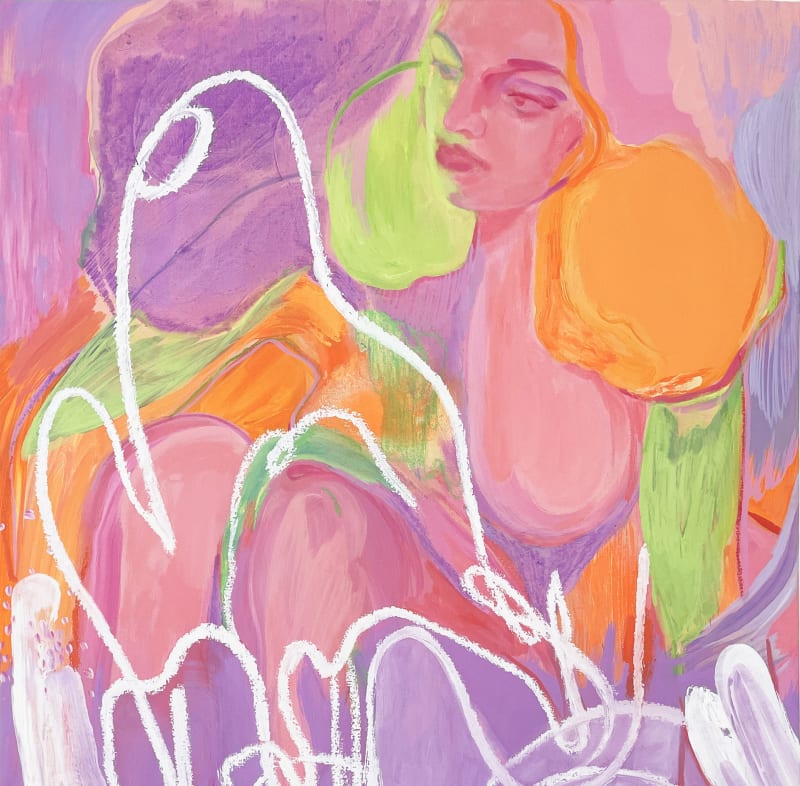

Dreamy female forms appear amid vivid, swirling landscapes, their limbs entwined with the translucent, ghostlike silhouettes of swans. British artist Amy Beager draws on the language of fairy tale and myth to create darkly romantic scenes that blur the boundaries between abstraction and figuration, fantasy and reality. Swan Maidens, her first solo exhibition with Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, centres around the story of a woman – half human, half swan – torn between the mortal and immortal worlds. At once haunting and beautiful, the paintings envision different interpretations of the folklore reflecting on ideas around power, seduction, desire, entrapment, freedom and loss.

While Beager may plan the rough positioning of her figures, the overall composition, the colours, lines and textures, develop through the painting process, allowing her the freedom to experiment with different ways of conveying the narrative. This approach results in fluid, sweeping brushstrokes, rough pastel gestures, translucent layers of paint and soft, undulating forms that appear to melt into one another, confusing our sense of perspective and creating a powerful impression of movement. In this latest body of work, natural elements – waterways, trees, long grasses – converge with the supernatural to create a liminal space, an in-between. This is perhaps most apparent in large scale diptych Glow. On the left hand side of the canvas, there is a voluptuous female figure, rendered in rich tones of orange and pink while on the right hand side there are two barren trees with their branches reaching upwards in thin spikes. The woman is almost godlike in scale and yet her body is obscured by thick, wide brushes of paint – as if she is being engulfed by the landscape. Here, the luminous, spectral silhouette of the swan, its wings spread and neck reaching into the distance becomes a powerful symbol of longing.

Elsewhere the swan appears more abstracted, its presence hinted at through a plume of white feathers, a floating head, rough touches of white. The Sink, for example, depicts the woman’s body submerged in a green liquid-like substance. We see the outline of her face turned upwards at the bottom of the canvas, while her arms reach into the pink sky. Though the swan itself is absent, the woman’s hands appear bathed in a strange white, luminous light, perhaps indicative of a fading supernatural power as she falls into another world. In this sense, the spirit of the swan is both a curse and blessing: it is a form of entrapment but also a life source, it is what makes her unique. This is the crux of the swan maiden’s romantic tragedy but it also reflects on real world issues around gender politics and belonging. Indeed, though each painting possesses a distinct emotional narrative, they share a sense of restlessness or rather, a refusal to be still.